Now 10% off all Ergolash lashing straps save now! Voucher code: ergo10 | Valid until 31.05.2025

It is a generally known fact that with the tie-down lashing method, some circumstances that cannot be precisely weighed up by the user can influence the securing force. One of these circumstances is the distribution of the pre-tensioning force (STF) from the ratchet side to the opposite side of the load.

Most of those involved know from their gut feeling that less arrives on the opposite side than on the ratchet side. The question that immediately arises is: how much power is lost and can I calculate this?

This is precisely where the discussion between supporters of EN-12195-1 and VDI-2700ff begins. Both sides are staffed with experts, with the difference that only Germans are involved in the VDI-2700ff, but those from 27 countries are involved in the EN-12195-1. Unfortunately, those involved on both sides lose sight of the driver and the shipper, who are supposed to put the sometimes very theoretical considerations into practice.

In the following article, I will try to clear up the jungle a little and present it in a way that is easy to grasp for practitioners. I hope I succeed. But even I am not infallible.

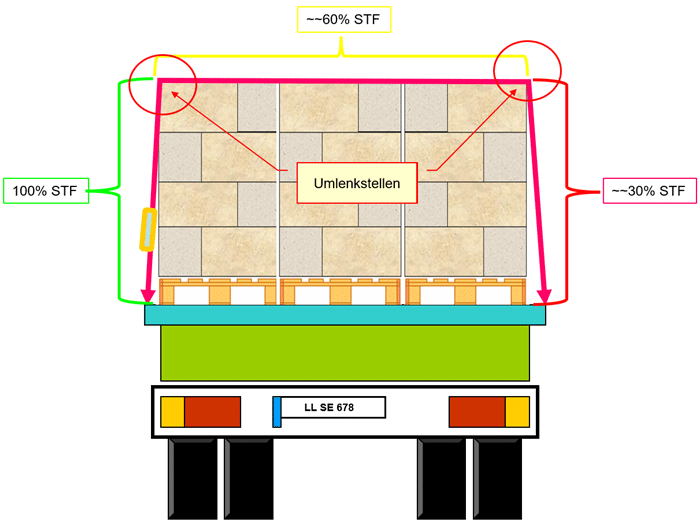

With the tie-down lashing method, a belt is placed over the load, the hooks of the fixed and loose ends are hooked in and then the pre-tensioning force is applied with the ratchet. The percentages in the diagram are fictitious and are only intended to show that the pretensioning force applied over the corners of the load is becoming less and less.

Regardless of how high the preload force is, it is generally divided into at least three areas:

If there are more than two deflection points, the clamping force distribution also becomes more fragmented.

VDI-2700 Sheet 2 Edition 07-2014 refers to the transmission coefficient (k), which can assume a value of k=2.0 under certain circumstances. These specific circumstances would be a pre-tensioning force indicator at the slack end or a belt with two ratchets. In practice, a value of k=1.8 is recommended. In my view as a practitioner, that is a very sporting idea. Edge gliders (edge protection angles) should generally be used. The remaining force is calculated using the formula according to Euler:Fres = F * e -µ*α.

Will the general shippers and drivers be able to cope with this? Rather no!

EN-12195-1 edition 01-2021 refers to the safety factor (fs) because it assumes that the preload force is the same on both sides. The safety factor is used to compensate for uncertainties when securing loads. To the sides and to the rear it should be assumed to be fs=1.1 and to the front fs=1.25.

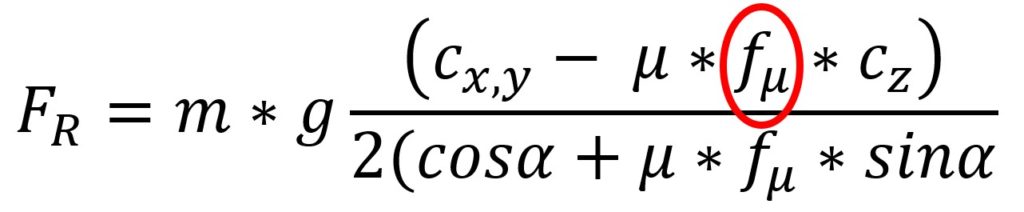

The equation for calculating the pre-tensioning force of a lashing is as follows:

This is the formula for calculating the securing force. The safety factor (fs) is added at the end of the usual calculation. This means that the calculated preload force is increased by 10% or 25% across the board.

This is the formula for calculating the frictional force for direct lashing.

The coefficient of friction µ is multiplied by the factor fµ=0.75. This means that it is reduced by 25%.

Example:

Load weight = 1,000kg

Coefficient of friction µ=0.3

1,000daN * 0.3 = 300daN.

1,000daN * 0.3 * 0.75 = 225daN

Reducing the frictional force automatically results in an increase in the securing force, which is intended to compensate for uncertainties.

EN-12195-1 also attempts to balance out the uncertainties with mathematical considerations, whereby the factors themselves also contain an uncertainty. Nobody knows exactly whether the factors are correct. In principle, however, it is better to work with safety than not to. Such safety factors have always been used in seafaring to safeguard against imponderables. So this is nothing new.

How can this problem be put into practice?

Option 1: the responsible person according to §9(2) OWiG, who is appropriately trained and knowledgeable, takes a calculator and calculates each individual charge. From a legal/physical point of view, this is the safest method. The measures should be documented.

Variant 2: the responsible person in accordance with §9(2) OWiG ensures that certain conditions are met. These considerations result from the calculations of variant 1, which could be:

Experience shows that most loads can be transported safely when using variant 2 and the risk is reduced to a minimum.

The considerations described above do not release the person responsible, which in any case is the management, from organizing the entire loading process in their own area in a comprehensible manner. This can be used to counter the accusation of “gross organizational negligence pursuant to §130OWiG”. If inadequate load securing results in a situation that goes beyond an administrative offense and becomes a criminal offense, it must be demonstrated what considerations and measures were taken to avoid or prevent the situation. A good basis is the study of VDI-2700 Sheet 5 “Quality Management Systems”. Here, the entire process is broken down into thin, comprehensible slices that then need to be organized.

It is best to start immediately with the measures described if they have not already been taken.

I wish everyone happy working and a lucky hand.

Yours, Sigurd Ehringer

Next Post >>

Episode 42: Wedges for load securing

Sigurd Ehringer

✔ VDI-zertifizierter Ausbilder für Ladungssicherung ✔ Fachbuch-Autor ✔ 8 Jahre Projektmanager ✔ 12 Jahre bei der Bundeswehr (Kompaniechef) ✔ 20 Jahre Vertriebserfahrung ✔ seit 1996 Berater/Ausbilder in der Logistik ✔ 44 Jahre Ausbilder/Trainer in verschiedenen Bereichen —> In einer Reihe von Fachbeiträgen aus der Praxis, zu Themen rund um den Container und LKW, erhalten Sie Profiwissen aus erster Hand. Wie sichert man Ladung korrekt und was sind die Grundlagen der Ladungssicherung? Erarbeitet und vorgestellt werden sie von Sigurd Ehringer, Inhaber von SE-LogCon.

Rothschenk assortment

Our customer center has only one goal: to turn your problems into solutions. Whether standard stowage cushions, bestsellers or load securing personally tailored to your needs -. we accompany you consistently from A as in field service to Z as in certification. That is our promise to you, as a leader in our industry.

We attach great importance to professional cargo securing. That is why we have our own production, which ensures reliable operation through modern manufacturing technologies and strict quality control. Thus, we offer our customers a comprehensive and high-quality range of services in the field of transport logistics.

DIN ISO 9001:2015, EMAS and Ecovadis are not foreign words to you? Then it's time to work with the best.

You don't take any risks with us - we have been awarded the Platinum Medal on the EcoVadis sustainability rating platform.

As a load securement company, we are proud to have several certifications that validate our sustainability efforts and our commitment to environmental protection and social responsibility. For you as a purchaser, this means that we demand and promote the implementation of high environmental and social standards both within the company and along the supply chain.

You are currently viewing a placeholder content from Google Maps. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More Information